In August 2024, 80% of Venezuela was plunged into darkness by a power outage that lasted around 12 hours. Such disruption has continued since then, and blackouts in Venezuela can last for days. The existing “load management plan” involves scheduled four-hour power cuts in different regions to reduce pressure on the electricity system. But it has not been able to prevent generation and distribution systems being overwhelmed.

This year, the government implemented new restrictions to save energy, ordering all public offices to work only half days between March and May 2025. It said this was due to “the climate emergency that has led to rising temperatures worldwide … affecting the water level of the reservoirs that generate electricity in the Andean region”.

But in May, President Nicolás Maduro pointed to his political opposition, and even the global hacking collective Anonymous, whose affiliation is unknown, accusing them of an attack on the Simón Bolívar Hydroelectric Power Plant, which generates 60% of Venezuela’s electricity.

Various experts state that the power failures are not caused by sabotage, but rather by a lack of maintenance, deforestation around hydroelectric facilities and poor management. These problems remain six years after a week-long blackout in 2019 that left several states without power for at least five days and ushered in an era of scheduled outages, which continue today.

Venezuela’s electricity system relies mainly on hydropower in the south of the country, especially from enormous dams surrounded by primary forests.

The system had operated efficiently for decades, with backup from gas and oil power plants and private management. However, the nationalisation process that began in 2007 under previous president Hugo Chávez was faced with problems such as lack of investment and loss of experienced employees after the politicisation of its management by officials unfamiliar with the energy sector.

Now, power outages are part of everyday life in Venezuela, leading thousands of people to purchase generators, rechargeable light bulbs and solar chargers for mobile phones.

A solar future in Mérida?

In June 2024, as part of his third presidential election campaign, Maduro announced a plan to generate 3,000 megawatts (MW) of solar energy in the Venezuelan Andes, with the support of Turkey, Russia, India and China.

After controversially claiming victory in the election, Maduro used a television broadcast to formally open a smaller project in January: a solar farm located in El Vigía, north-western Mérida state, with 1,207 panels “assembled on Venezuelan territory”. Marielys Sacipa, territorial manager of state power company Corpoelec Mérida, claims that this is the largest in Venezuela. The farm provides electricity to pumping systems that supply water to 47 apartment blocks and more than 2,200 families.

That same month, the governor of Mérida, Jehyson Guzmán, signed an agreement with Chinese company Green Full to start construction on another solar project, which he said would be the “largest solar park in Venezuela”. Guzmán said that it will have a capacity of 50MW, which would meet at least 40% of the state’s electricity demand.

This project will be installed at the Don Luis Zambrano thermal power plant in El Vigía, a city in north-western Mérida, which has been riddled with problems since opening in 2014. Despite an investment of at least USD 31 million in 2018, it has been out of service since 2020. Representatives of the firm toured the facilities together with local authorities in January, but no information was provided on the amount of Green Full’s investment or other details of the project.

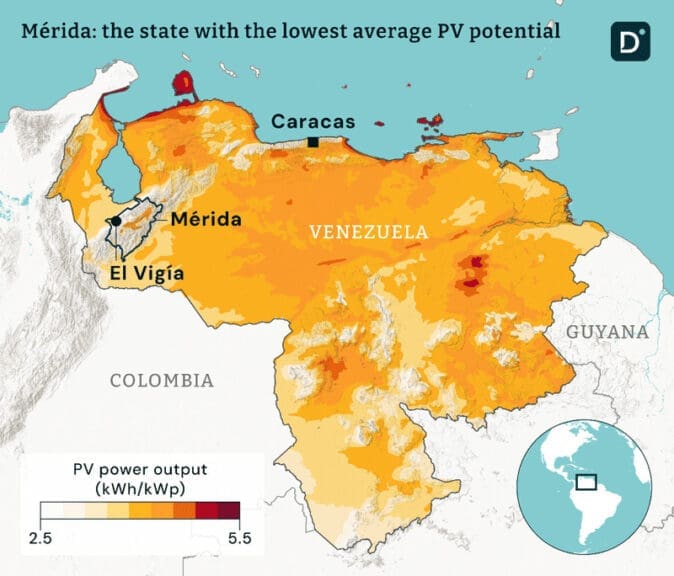

The curious thing about the state of Mérida is that it has the lowest average photovoltaic (PV) potential in the country, according to the Global Solar Atlas. No one Dialogue Earth spoke to could identify why it was chosen for these solar power investments.

Solar farms without energy

On several occasions, politicians have claimed a new solar plant to be the first in Mérida, and also the biggest. But the very first was actually a 2009 project launched as part of Hugo Chavez’s Sembrando Luz (“Sowing Light”) programme to bring solar and wind energy to remote areas.

One of the first rural communities to benefit from the programme was El Quinó, in the Sierra Nevada National Park. In November 2024, more than 15 years after the solar panels were installed in that community, social media reports on maintenance works stated it was still providing power to some 200 people.

Other similar installations in Mérida have not been so fortunate. In Páramo de Los Conejos, a rural community located an eight-hour walk from the state capital, a wind and solar power generation system was installed in 2013. It aimed to benefit 150 people, at a cost of more than USD 250,000, according to the National Electricity Corporation.

El Vigía farm is another ‘red elephant’ that was presented with great fanfare but ended up serving only a very small group of residents

Dialogue Earth has learned the system operated at 100% until January 2023. But misuse, combined with a lack of maintenance and replacement equipment, means it currently generates electricity for just one school and four houses.

These are not the only obstacles to harnessing solar energy in Mérida. The El Vigía farm, officially launched by Maduro in January but which had in reality begun operations last year, lacks the batteries needed to store energy and maintain distribution when the sun is not shining. “After they inaugurated the panels, they – the government – said they would bring the batteries, but it’s been almost a year now,” said a nearby resident who requested anonymity for fear of reprisals.

Others say the farm was never fully installed. Another local resident said: “It hasn’t worked in my tower because it wasn’t connected to the water pumping system. In my opinion, it’s another ‘red elephant’ [referring to the colours of the governing party and its unfinished works] that was presented with great fanfare but ended up serving only a very small group of residents.”

The government, which is often accused of lacking transparency, has not published information about the investment, equipment or companies involved in the project.

In February 2023, Guzmán, the governor of Mérida, presented what he also referred to as the first public solar panel plant in Mérida, located in the rural area of Llano de El Anís. This small “pilot project,” which reportedly operates at only 40% of its capacity, consists of 135 solar panels and generates electricity for only 17 homes, as well as a health centre and a school.

Although Guzmán said during its inauguration that “more homes and the public lighting system can still be connected”, more than two years later, it remains in the “start-up” phase.

Dialogue Earth visited the area and attempted to arrange access to the plant, but did not receive authorisation.

Slow progress and failure of the energy transition

Between 2005 and 2009, under the Sembrando Luz programme, 850 solar systems were installed in schools, health facilities, community centres and border posts in isolated communities in Venezuela. In addition, nearly 1,900 homes, 300 water-treatment plants, pumps and desalination plants were electrified, as Dialogue Earth has previously reported.

The programme served just over 200,000 people in 932 communities that had no electricity. Sembrando Luz later installed 2,000 PV systems between 2009 and 2011. In the following two years, it reported only 200 systems, and finally only 50 in 2013. The fall in oil prices put an end to the programme.

This coincides with the abandonment of large energy-transition projects, such as the wind farms in Paraguaná, La Guajira and Margarita. After billions of dollars of investment, these have been looted and largely abandoned, and now hardly produce electricity. Neither has the solar farm installed in 2015 by a Chinese company on the idyllic Caribbean island of Los Roques. The government announced in 2023 that it would reactivate the facility after eight years of abandonment and without it having generated electricity, but it remains out of service.

China’s investment losses in Venezuela have been extensive, leading the country to suspend new disbursements and loans in Venezuela in 2016. A Connectas report revealed that 17 Chinese projects with a total investment of USD 22 billion had failed to meet their objectives.

A report by Transparencia Venezuela released in March revealed that by the end of 2024, very few China-backed fossil-fuel projects were actually producing. Among the eight Venezuela-China oil and gas joint ventures with Chinese capital, only two are producing, but far below their targets, it noted.

The panels arrive in El Vigía

In April 2025, Sacipa, of Corpoelec Mérida, reported on her Instagram account that Chinese specialists from Green Full had returned to the site where the solar panels will be installed as part of the first phase, which will take “several months”.

On 29 May, Sacipa posted another Instagram Reel showing containers travelling along a road: these would carry the 94,000 solar panels to be installed with China’s support. However, it is not clear whether they were manufactured in Venezuela or imported.

Although Venezuela has its own solar-panel and wind-turbine factory, the Venezuelan Renewable Energy Unit (Unerven), its production is so small-scale that in order to fulfil the promises of the new solar farm in Mérida, they will have to import at least some panels. This is according to the president of the Venezuelan Renewable Energy Council, Ariadne Serrano, and an investigation by Climate Tracker.

Following regional elections in May, Mérida has a new governor, Arnaldo Sánchez. That means his predecessor’s wish for a nuclear reactor in the Andean region – backed by China and Russia – is up in the air. It remains to be seen what the future holds for other projects in the area.

What does seem certain is that the blackouts will continue. In May 2025, Chevron’s licence to extract oil in Venezuela expired, and the US government ordered it to withdraw from the country. This will not only result in a loss of USD 150-200 million per month, increasing inflationary pressure and the exchange rate, but will also severely cut the supply of diluents and fuel, which are essential for operating gas and oil power plants. Other companies operating seven oil wells have also halted their activities, mainly as a result of US sanctions on the country.

In Mérida, opportunities to generate sustainable, clean solar energy are being created, but it remains to be seen whether this will be a continuous effort or once again fall by the wayside.

This post was first published on Dialogue Earth and republished here under a Creative Commons BY NC ND License. Read the original article.